A groundbreaking study by Just Facts has discovered that after accounting for all income, charity, and non-cash welfare benefits like subsidized housing and food stamps, the poorest 20 percent of Americans consume more goods and services than the national averages for all people in most affluent countries. This includes the majority of countries in the prestigious Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), including its European members. In other words, if the US “poor” were a nation, it would be one of the world’s richest.

Notably, this study was reviewed by Dr. Henrique Schneider, professor of economics at Nordakademie University in Germany, and the chief economist of the Swiss Federation of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises. After examining the source data and Just Facts’ methodology, he concluded: “This study is sound and conforms with academic standards. I personally think it provides valuable insight into poverty measures and adds considerably to this field of research.”

The “Poorest” Rich Nation?

In a July 1 New York Times video op-ed that decries “fake news” and calls for “a more truthful approach” to “the myth of America as the greatest nation on earth,” Times producers Taige Jensen and Nayeema Raza claim the US has “fallen well behind Europe” in many respects and has “more in common with ‘developing countries’ than we’d like to admit.”

“One good test” of this, they say, is how the US ranks in the OECD, a group of “36 countries, predominantly wealthy, Western, and Democratic.” While examining these rankings, they corrupt the truth in ways that violate the Times’ op-ed standards, which declare that “you can have any opinion you would like,” but “the facts in a piece must be supported and validated,” and “you can’t say that a certain battle began on a certain day if it did not.”

The Times is not merely wrong about this issue but is also reporting the polar opposite of reality.

A prime example is their claim that “America is the richest country” in the OECD, “but we’re also the poorest, with a whopping 18% poverty rate—closer to Mexico than Western Europe.” That assertion prompted Just Facts to conduct a rigorous, original study of this issue with data from the OECD, the World Bank, and the US government’s Bureau of Economic Analysis. It found that the Times is not merely wrong about this issue but is also reporting the polar opposite of reality.

Poor Compared to Whom?

The most glaring evidence against the Times’ rhetoric is a note located just above the OECD’s data for poverty rates. It explains that these rates measure relative poverty within nations, not between nations. As the note states, the figures represent portions of people with less than “half the median household income” in their own nations and thus “two countries with the same poverty rates may differ in terms of the relative income-level of the poor.”

The OECD’s poverty rates say nothing about which nation is “the poorest.” Nonetheless, this is exactly how the Times misrepresented them.

The upshot is laid bare by the fact that this OECD measure assigns a higher poverty rate to the US (17.8 percent) than to Mexico (16.6 percent). Yet World Bank data show that 35 percent of Mexico’s population lives on less than $5.50 per day, compared to only 2 percent of people in the United States.

Hence, the OECD’s poverty rates say nothing about which nation is “the poorest.” Nonetheless, this is exactly how the Times misrepresented them.

The same point applies to broader discussions about poverty, which can be measured in two very different ways: (1) relative poverty or (2) absolute poverty. Relative measures of poverty, like the one cited by the Times, can be misleading if the presenter does not answer the question: Poor compared to who? Absolute measures, like the number of people with income below a certain level, are more straightforward and enlightening.

Unmeasured Income and Benefits

To accurately compare living standards across or within nations, it is necessary to account for all major aspects of material welfare. None of the data above does this.

The OECD data is particularly flawed because it is based on “income,” which excludes a host of non-cash government benefits and private charity that are abundant in the United States. Examples include but are not limited to:

- Health care provided by Medicaid, free clinics, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program

- Nourishment provided by food stamps, school lunches, school breakfasts, soup kitchens, food pantries, and the Women’s, Infants’ & Children’s program

- Housing and amenities provided through rent subsidies, utility assistance, and homeless shelters

The World Bank data includes those items but is still incomplete because it is based on government “household surveys,” and US low-income households greatly underreport both their income and non-cash benefits in such surveys. As documented in a 2015 paper in the Journal of Economic Perspectives entitled “Household Surveys in Crisis”:

- “In recent years, more than half of welfare dollars and nearly half of food stamp dollars have been missed in several major” government surveys.

- There has been “a sharp rise” in the underreporting of government benefits received by low-income households in the United States.

- This “understatement of incomes” masks “the poverty-reducing effects of government programs” and leads to “an overstatement of poverty and inequality.”

Likewise, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis explains that such surveys “have issues with recalling income and expenditures and are subject to deliberate underreporting of certain items.” The US Census Bureau says much the same, writing that “for many different reasons there is a tendency in household surveys for respondents to underreport their income.”

There is also a wider lesson here. When politicians and the media talk about income inequality, they often use statistics that fail to account for large amounts of income and benefits received by low- and middle-income households. This greatly overstates inequality and feeds deceptive narratives.

Relevant, Reliable Data

The World Bank’s “preferred” indicator of material well-being is “consumption” of goods and services. This is due to “practical reasons of reliability and because consumption is thought to better capture long-run welfare levels than current income.” Likewise, as a 2003 paper in the Journal of Human Resources explains:

- “[R]esearch on poor households in the U.S. suggests that consumption is better reported than income” and is “a more direct measure of material well-being.”

- “[C]onsumption standards were behind the original setting of the poverty line,” but governments now use income because of its “ease of reporting.”

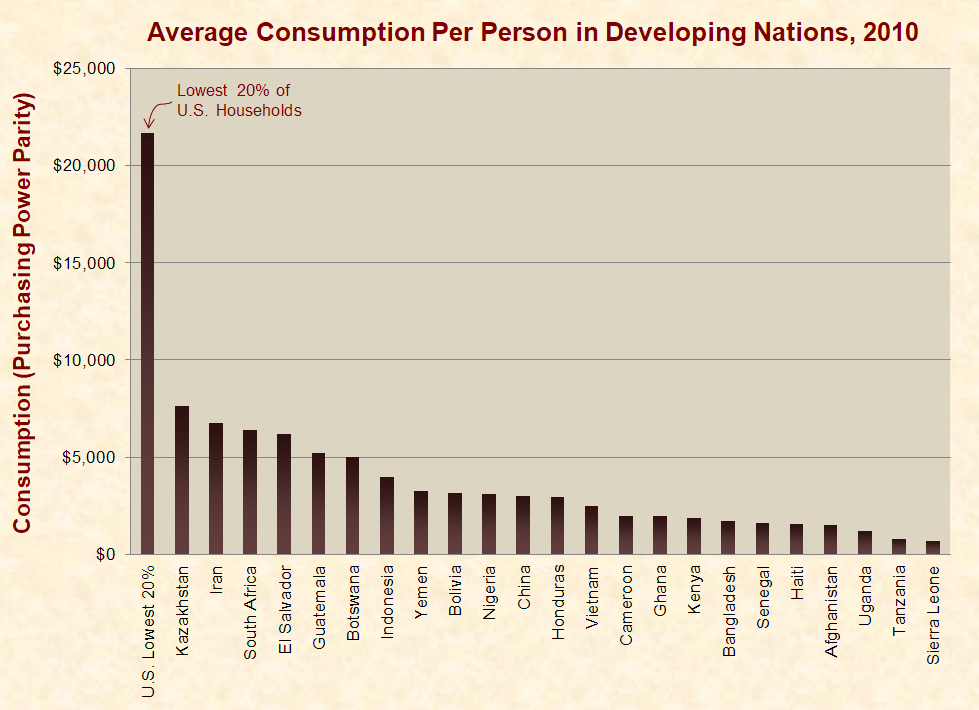

The World Bank publishes a comprehensive dataset on consumption that isn’t dependent on the accuracy of household surveys and includes all goods and services, but it only provides the average consumption per person in each nation—not the poorest people in each nation.

However, the US Bureau of Economic Analysis published a study that provides exactly that for 2010. Combined with World Bank data for the same year, these datasets show that the poorest 20 percent of US households have higher average consumption per person than the averages for all people in most nations of the OECD and Europe:

The high consumption of America’s “poor” doesn’t mean they live better than average people in the nations they outpace, like Spain, Denmark, Japan, Greece, and New Zealand. This is because people’s quality of life also depends on their communities and personal choices, like the local politicians they elect, the violent crimes they commit, and the spending decisions they make.

For instance, a Department of Agriculture study found that US households receiving food stamps spend about 50 percent more on sweetened drinks, desserts, and candy than on fruits and vegetables. In comparison, households not receiving food stamps spend slightly more on fruits & vegetables than on sweets.

The fact remains that the privilege of living in the US affords poor people more material resources than the averages for most of the world’s richest nations.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that the privilege of living in the US affords poor people more material resources than the averages for most of the world’s richest nations.

Another important strength of this data is that it is adjusted for purchasing power to measure tangible realities like square feet of living area, foods, smartphones, etc. This removes the confounding effects of factors like inflation and exchange rates. Thus, an apple in one nation is counted the same as an apple in another.

To spot-check the results for accuracy, Just Facts compared the World Bank consumption figure for the entire US with the one from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. They were within 2 percent of each other. All of the data, documentation, and calculations are available in this spreadsheet.

In light of these facts, the Times’ claim that the US has “more in common with ‘developing countries’ than we’d like to admit” is especially far-fetched. In 2010, even the poorest 20 percent of Americans consumed three to 30 times more goods and services than the averages for all people in a wide array of developing nations around the world.

These immense gaps in standards of living are a major reason why people from developing nations immigrate to the US instead of vice versa.

Why Is the US So Much Richer?

Instead of maligning the United States, the Times could have covered this issue in a way that would help people around the world improve their material well-being by replicating what makes the US so successful. However, that would require conveying the following facts, many of which the Times has previously misreported:

- High energy prices, like those caused by ambitious “green energy” programs in Europe, depress living standards, especially for the poor.

- High tax rates reduce incentives to work, save, and invest, and these can have widespread harmful effects.

- Abundant social programs can reduce market income through multiple mechanisms—and as explained by President Obama’s former chief economist Lawrence Summers, “government assistance programs” provide people with “an incentive, and the means, not to work.”

- The overall productivity of each nation trickles down to the poor, and this is partly why McDonald’s workers in the US have more real purchasing power than in Europe and six times more than in Latin America, even though these workers perform the same jobs with the same technology.

- Family disintegration driven by changing attitudes toward sex, marital fidelity, and familial responsibility has strong, negative impacts on household income.

- In direct contradiction to the Times, a wealth of data suggests that aggressive government regulations harm economies.

Many other factors correlate with the economic conditions of nations and individuals, but the above are some key ones that give the US an advantage over many European and other OECD countries.

In reality, the US is so economically exceptional that the poorest 20 percent of Americans are richer than many of the world’s most affluent nations.

“The Truth Is Worth It”

The Times closes its video by claiming that “America may once have been the greatest, but today America, we’re just okay.” In reality, the US is so economically exceptional that the poorest 20 percent of Americans are richer than many of the world’s most affluent nations.

Last year, the Times adopted a new slogan: “The truth is worth it.” Yet, in this case, and others, it has twisted the truth in ways that can genuinely hurt people. The Times makes other spurious claims about the US in this same video, which will be deflated in future articles.

James D. Agresti

James D. Agresti is the president and cofounder of Just Facts, a think tank dedicated to publishing rigorously documented facts about public policy issues.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. August of 2019. Read the original article.

FEE’s mission is to inspire, educate, and connect future leaders with the economic, ethical, and legal principles of a free society. These principles include: individual liberty, free-market economics, entrepreneurship, private property, high moral character, and limited government.